Here in this time of a world pandemic, and in this time of a call for a deeper justice, so much is in motion, aswirl.

In my own life, I feel these swirls of change as my 20 year old daughter makes her plans to leave home, as I grieve the death of a beloved mother, dear to me, and as I adjust to a season where we continue to be far away from our people.

Usually, I see my loved ones in the winter holidays and then again in the summer, when I visit my large, extended Italian-Polish family in Ohio. But this year, visiting them is not an option. My father has a heart condition, and with my parents’ age, it’s too risky; they are not receiving guests.

When attachment hunger arises as longing

These past months, these longings for my kin have honed themselves to a sharp point. In the evenings, I will often put on Jeopardy while cooking dinner or puttering around the living room.

Jeopardy reminds me of my mom and dad, for I often watch it with them. Listening to Alex Trebek’s soothing voice, I feel that thread connecting me to them, heart to heart. In his voice, and in the Jeopardy theme song, I hear a lullaby.

I also find myself calling my parents often, to talk for no reason in particular. I ask about my dad’s raspberry plants; his battle with the chipmunks over his bird feeders; my mom’s studies to regain her psychologist’s license after 10 years away, caretaking for ageing parents.

When I went shopping this weekend for a nightgown, I found myself in the pajama section with the other grandmothers, thumbing through the housecoats, what all the elder women in my family have worn for generations.

I bought a pale blue nightgown to ship to my 90 year old great Aunt Nancy, who lives in a nursing home in Pennsylvania.

I hang my laundry on my line with my grandmother’s wooden clothes pins and I talk to her. I cook her marina sauce and bring the smells of her house into my kitchen. I have one of her shirts, and I tuck myself into it, imagining I can still smell her on the fabric.

I miss her, dead last year after living to an outstanding 96.

If you ask me what I want to be when I grow up, I would tell you that my dream is to be the women in my life. I long to be my elders: my grandmothers, my aunts, my mother, my great aunts, and all the other mothers, not of blood, but of equal kin, who are a part of my inner family.

The longing for connection

I imagine you have your own stories to share, the lullabies that remind you of your connections to life and to your loved ones, and the ways you hold love close: the games, movies, shows, music, hobbies, plants, trees, and yes, foods, that bring you into connection to those you love.

All these things are ties to your sacred Mothers and Fathers – both those of blood, and those of heart – who inhabit your inner village, those beings who have nurtured the Holy Child who resides within you.

What are these threads that tie us to our loved ones? To our families – both the ones we are born into, and those we make ourselves?

Right now I’m in the midst of teaching this year’s When Food is Your Mother class. I’m moved, touched, and awed by the group, by the way they support each other, by their tender courage, and their willingness to give words to our poignant longings for mothering, for our inner and outer Mothers, in all her forms.

Our needs do not go away but awry

This longing – for mothering, for connection to our loved ones, for contact and closeness, for the nurturing and holding of our inner lives – is something I feel moved to protect, for it is often pathologized in our modern culture.

Sometimes is seems as if our human vulnerability and neediness is portrayed as something we should strive to control or minimize.

As if to hunger is to sin. As if to feed is wrong.

But when this core need for connection is dismissed and shamed, it does not go away, but awry. It goes sideways into obsessions, compulsions, and overdoing.

Then we personalize these sideways pursuits, thinking, “There’s something wrong with me.”

Overeating or overdoing or overworking becomes a story of shame we tell about ourselves rather than the natural consequence when a culture becomes disconnected from the holiness of our inherent dependence, from the heart, and from the Mother.

We are born with ‘primary satisfactions’

One of my most beloved books on the science of human relationship is A General Theory of Love. In this book the authors describe the challenges when we live in an ‘achievement based culture’ rather than an ‘attachment based’ one.

In the West, we tend to prize achievement, and its bedfellows: autonomy, individualism, personal succes, and individuation over relationship, connection and closeness.

I think of how therapist and soul weaver Francis Weller says it: how each human being is born with primary satisfactions.

Our primary satisfactions are simple: connection, community, a sense of purpose. Joy, celebration, ritual. Sensuality, expression; relationships with others and with our living world.

When these primary satisfactions go unmet, that is when we become driven by secondary satisfactions: success, status, money beyond our financial needs. The prize, the win, the hit.

This is when our needs become complex, when we wreak havoc on our world, our planet, on ourselves, and on each other.

The longing for connection is holy

If there’s anything that When Food is Your Mother has taught me, it’s that our primary satisfactions, our longing for attachment and relationship is inborn within us, and is something sacred, trustworthy, and true.

For who amongst us wants to live in a motherless, disconnected, disembodied world?

But we do not trust our hungers. In our modern world, we twist this cry of the heart.

We pathologize the call to connect, our loneliness, our desire for relationship, and the instinctive ways we hold love close. We call it ‘neediness’ – as if our inherent neediness is something shameful we should overcome.

Your attachment cries are an invitation to connect

When we feel separate and disconnected, our hearts let us know – what developmental psychology calls the attachment cry. It can be primal: a child crying for a mother, or an adult crying out for their lover. Spiritually, we feel this as a thirst for the Divine, for Life, and for meaning.

When we feel this cry, everything in us rises to connect.

All the ways we instinctively connect – through beloved foods, through remembered family recipes, through passed down stories and songs – are, in fact, rituals of remembrance and reconnection, responses to this cry.

These things are our lifeblood as human beings, what reassures our hearts that, no, we are not motherless, or fatherless, and that we do not live in a motherless world.

They hold us in the web of connection.

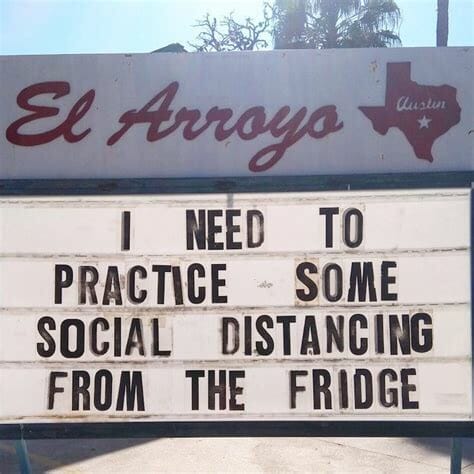

“I need to practice social distancing from my fridge”

The famed Mexican restaurant, El Arroyo, in Austin, Texas, is known for its humorous signs.

Yesterday, while riding my bike around my neighborhood, I saw a sign that said, “I need to practice social distancing from my fridge.”

I burst out laughing at the humor, but also felt its truth.

For as we socially distance from each other, food is one way we can – and do – hold love close. Food becomes a vehicle for those tender primary satisfactions.

Food has become the carrier of our heart’s cry.

If we honored the desire for food for what it really is, we would see, how each meal, each craving is not a source of shame, but a prayer in disguise.

Prayers in disguise

If this is true – if our cravings and longings are prayers – then holding love close is not pathology.

Cooking a meal that ties you to kin is not pathology.

Imbuing your life with ritual to remember your loved ones – both human and non human – is not pathology.

And longing for love and connection is not pathology.

And if this is so, perhaps the attachment cry – the loneliness, the longing, the missing, the wanting to hold close – is not pathology, either. Rather, it is what invites us into reconnection and remembrance: the thirst that invites us into relationship.

May we celebrate our hungers

So here in this time of physical separation, when so many of us are apart from our loved ones – not to mention our neighbors, co-workers, and communities – I pray that we may turn towards, rather than away from our longings.

For it is in turning toward our longings – attending to these attachment cries – that they can be fully received, honored, and met. Perhaps the answer lies in feeling our heart’s cries, more, not less, and trusting where and how they lead us.

For me, today, these cries just might lead me to make a pot of marinara sauce, blessed by the basil from my neighbor’s garden, blessed by my grandmother’s tutelage, and blessed by the tears of missing for my loved ones.

A prayer of blessing

So this is my covid prayer.

I pray that our need for human connection, rather than something messy to minimize, may be embraced as something holy.

I pray that we may celebrate our hungers: our longings for connection, for meaning, for relationship, for celebration, for all the many Grandmothers and Grandfathers who weave their ways through our lives.

I pray that our physical hungers may help us befriend our emotional and relational hungers, and turn towards them, in warmth and welcome.

And I pray that we may see these hungers as good; as very, very good: the sacred heartbeat, the weft of the great web of life.

In love, Karly

Karly,

It’s late and the fam is in bed. I just picked my computer up to edit a file and found myself on your website. What you have written here is magnificently beautiful! What a blessing you are in this world. I feel so nurtured by your loving human(kind)ness!! Thank you for being the voice that you are. A true witness to our humanness. So awesome. I feel love emanate from your every word. You are a WOW in my life!!

Hi Pat, thank you for sharing how this article moved you. I’m so glad that we can witness our humanness together, side by side, and with courage and heart.

Pat, thank you !

I’m a ditto to your comment.

Found Karli ..about an hour and a half ago and I’ve shared her twice.

I share your awe and reverence for Karli, putting to words our hearts longing and healing.

Am sorry to hear of the loss of your beloved mother. Sadly, when mine passed, I felt relief as well as loss. Perhaps she struggled with mental illness. We tried to heal the distance between us but she just was not incapable of seeing and encouraging the best of who I am; perhaps because I was my Dad’s shadow/angel and she resented. No women in my world was a loving hugging woman except for one aunt–thank God for her. Thank God for food as my mother.

Bravo Karli !!

from the bottom of my heart.

The expanse of your experience and knowledge is profound

For certain A breakthrough

Thank You Again

Cookies by by…

Hello Rhonda! I’m so glad to hear that these ideas are ‘food’ for you, as well. May we know our connections, and our thirst for connection.