These past weeks, as the weather where I live has turned to autumn, I’ve been harvesting seeds from the now spent sunflower plants in my garden.

As I receive these seeds from their fuzzy pods, cradling them in white paper packets of goodness to mail to friends, I’ve been thinking about something I read in biologist and mother Robin Wall Kimmerer‘s gorgeous book, Braiding Sweetgrass:

“In some Native languages the term for plants translates to ‘those who take care of us.’”

What a thought!

In her book, Robin writes about how many people are comfortable with the idea of loving the Earth – but uncomfortable and unacquainted with the idea that the Earth loves and cares for them.

This resonates with my experience. It almost feels silly – especially to my Western rational mind – to imagine the Earth as a living being with a generous heart.

And yet the abundance of sunflower seeds – hundreds of seeds, just from one flower! – feels like a living example of the way we are, indeed, loved and cared for by Her.

The absence and presence of love

These themes of love and loving, of offering care and being cared for, are common ones that we explore in our courses and offerings.

Many of us carry wounds, the residue of early and not so early experiences, where we felt an absence, rather than a presence, of love.

Often, these experiences of loss create a gap – place of separation that we try to then fill. We may fill this hole with food, or with achievement and success, or with relationships, or some other form of ‘success,’ care, or safety.

I know the ways I try to fill my own holes are endless, and oh, so endlessly creative!

Connecting to the ground of Mother

Connecting to the Mother – and to all the many ways we are mothered – is a powerful practice that can help mend these tender places of rupture. It can help soften this bond with food while deepening our bond with Life.

When my children were small, they had an album of fairy songs, Fairy Moon, gifted to them at a friend’s birthday party, that they listened to, over, and over, as young children are known to do.

My favorite song from the album, First Best Friend, tells the story of a mother and child, and the tenderness of this first friendship. One line in the song has stayed with me, all these years:

We are born to just one mother

but as we grow there are so many others. – Maria Sangiolo

As I listen to Maria’s words, I feel my heart open in wonderment to the many beings that have been ‘mothers’ to me – women and men alike who have mentored and cared (and challenged me), friends and wise women elders, and also the kin of animals and plants and trees and walking paths.

Likewise, I imagine many of your sacred mothers will also come to mind – even mothers like willow trees and sunflowers, pets and wild animals, sacred groves and mountain streams.

We are surrounded by Mothers

When this idea – that we are surrounded by Mothers, and that we are surrounded by mothering throughout the width and breadth of our lives – sinks in to fecund soil, something takes root in us.

We begin to pay attention, to notice all the shapes and forms of the Mother and the many ways she appears.

This can bring comfort as well as mercy – for sometimes, the mothering we receive comes from mothers not of our direct family line.

I’m reminded of Penny Harter‘s poem, When I Taught Her How to Tie Her Shoes. Here’s an excerpt:

A revelation, this student

already in high school who didn’t know

how to tie her shoes.

I took her into the book-room, knowing

what I needed to teach was perhaps more

important than Shakespeare or grammar,

guided her hands through the looping,

the pulling of the ends. After several

tries, she got it, walked out of there

empowered. How many things are like

that—skills never mastered in childhood,

simple tasks ignored, let go for years?

The seeds that lie dormant in our being

When I listen to this poem I’m struck by the many things – shoe tying and beyond – that lie dormant, skills or seeds of skills that have not yet fully come into being.

I’m also struck by the way that the author of this poem was a mother to this teenage girl.

And I’m struck by how both those who mother us – and those whom we, ourselves, mother – draw these dormant seeds out from the soil and into full-fleshed form.

“We are all mothers.”

We are tied together within the bonds of giving and receiving. As another mentor, co-authors Perdita Finn and Clark Parsons of The Way of the Rose write, “We are all called to be mothers.”

Your mothering may not arise in the shape of a literal mother, in birthing a child.

But the many acts of mothering are something we are each called to offer to a living being, whether it be plant, animal, or person; stone, community or cause.

Likewise, we are always being mothered. These gifts, too, may have unusual guises, or seem too simple.

In my own life, I can think of thousands of sunrises and sunsets, bird song and wildflowers that I’ve failed to notice!

We are not separate from Mothering

It’s easy to feel separate from the mother, and mothering, as if it’s something outside of ourselves, or something we don’t yet know how to do, like tying our shoes.

But the Mothering energy that nurtures and feeds and cares for life moves in our being.

The practice of paying attention – of beholding where we are mothered, and likewise, attending to those places that call for our care and devotion – is a powerful antidote to this disconnection.

It’s also one way we can soothe the separation that has us seeking solace and comfort in food, or consumption, or striving.

I’ve found that the more I attend, and the more I praise, and the more I notice, the more my heart and mind rests – and the more I already feel mothered.

The holes in my being feel less frightening (and frightened.) They exist, side by side, with love.

What if we are already mothered?

So today I leave you with these questions:

What if we are already mothered?

And what if we already know how to mother?

And what if we are already mothering?

And what if, as the song sings, there are many, many mothers? And how does paying attention to these acts of mothering change us?

To all the Mothers, and to all Mothering,

Karly

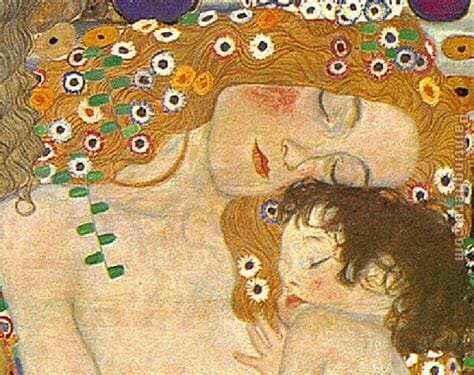

Top image: close up from The Three Ages of Woman by Gustav Klimt, 1905.